Explaining 'Migrant Middle'

What the phrase means and why it's important for us, today and tomorrow

India’s Diaspora

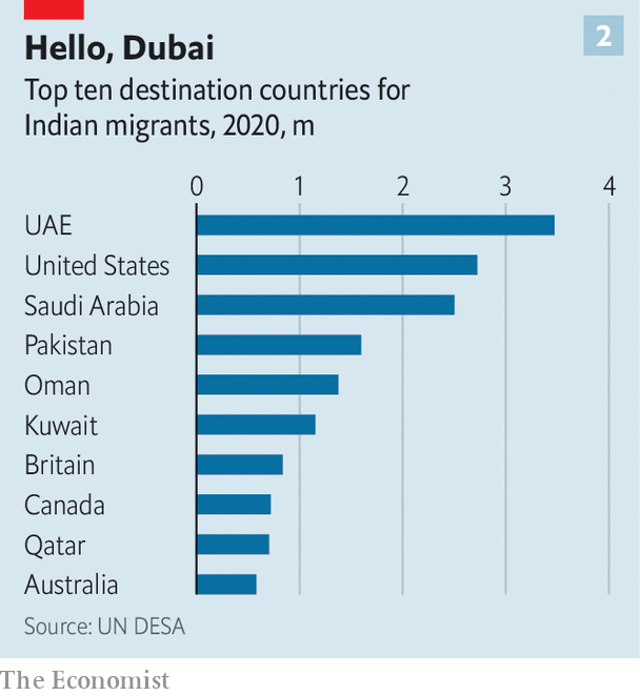

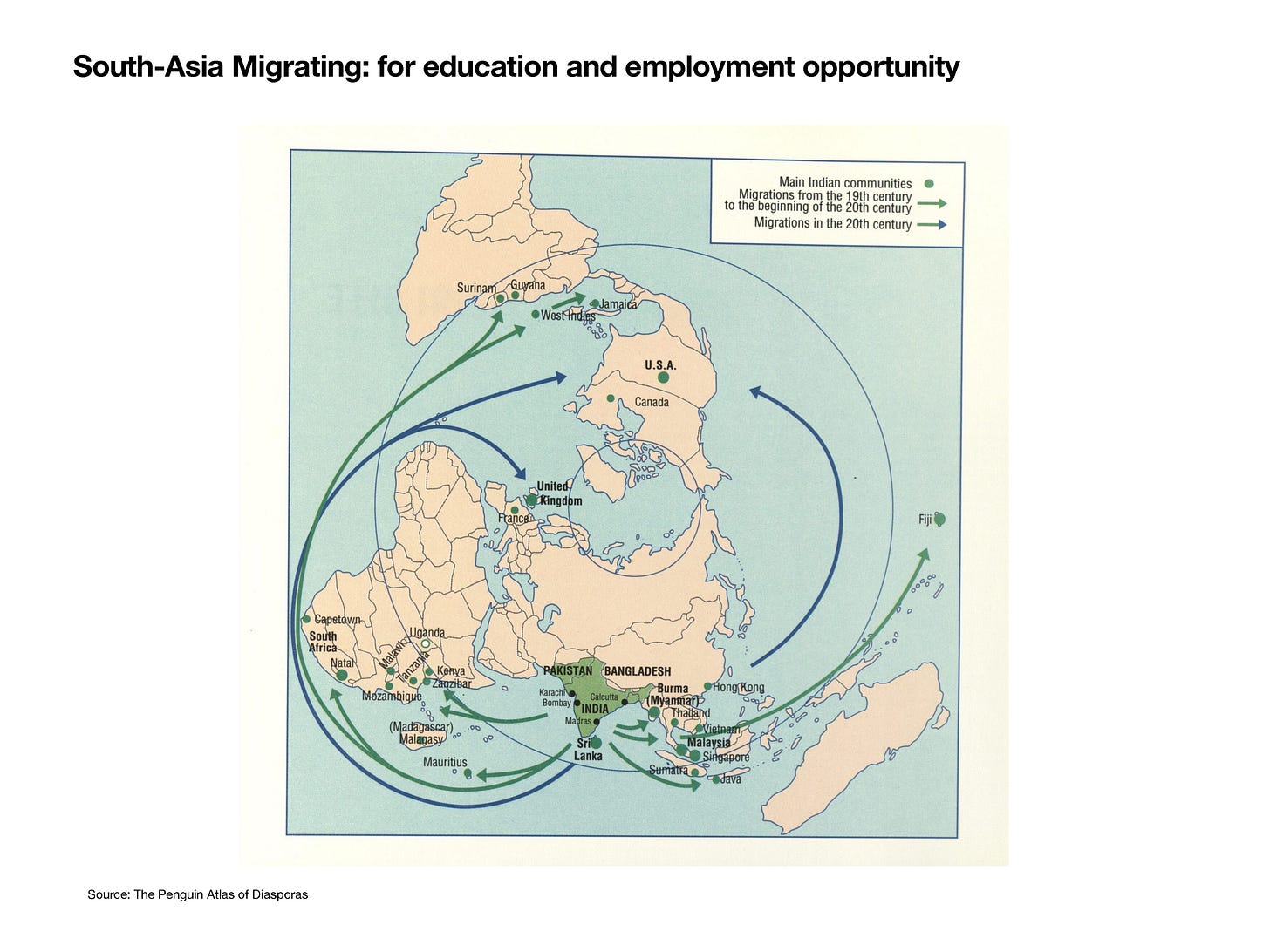

The landscape of migration, remittance (giving resources back to one’s homeland), and the Indian/American connection is stronger than ever. Today, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is meeting with US President Joe Biden at the White House. Last week, The Economist issued a timely article called “India’s Diaspora is bigger and more influential than any in history”. Written under the sub-heading ‘Making it as migrants’, the article states that “the Indian diaspora has been the largest in the world since 2010, and is a powerful resource for India’s government.”[1] With a lengthy insight into India’s independence in 1947 and the several waves of migration that departed from specific regions of India, recent statistics say that 2.7 million Indian migrants live in America as of 2020. As a comparison, there are 281 million migrants around the world today.

What’s important to note about this article is the relevance and contribution that the Indian-American diaspora has on our nation. And as stated, the quantities of Indian migrants of all caste are expected to grow. As we look to the future, the concept of ‘Migrant Middle’ will become more significant as the diaspora becomes more diverse, and as transnational connections between India and the US (complex as they are) shape real life places and spaces, both here and abroad.

Defining the phrase

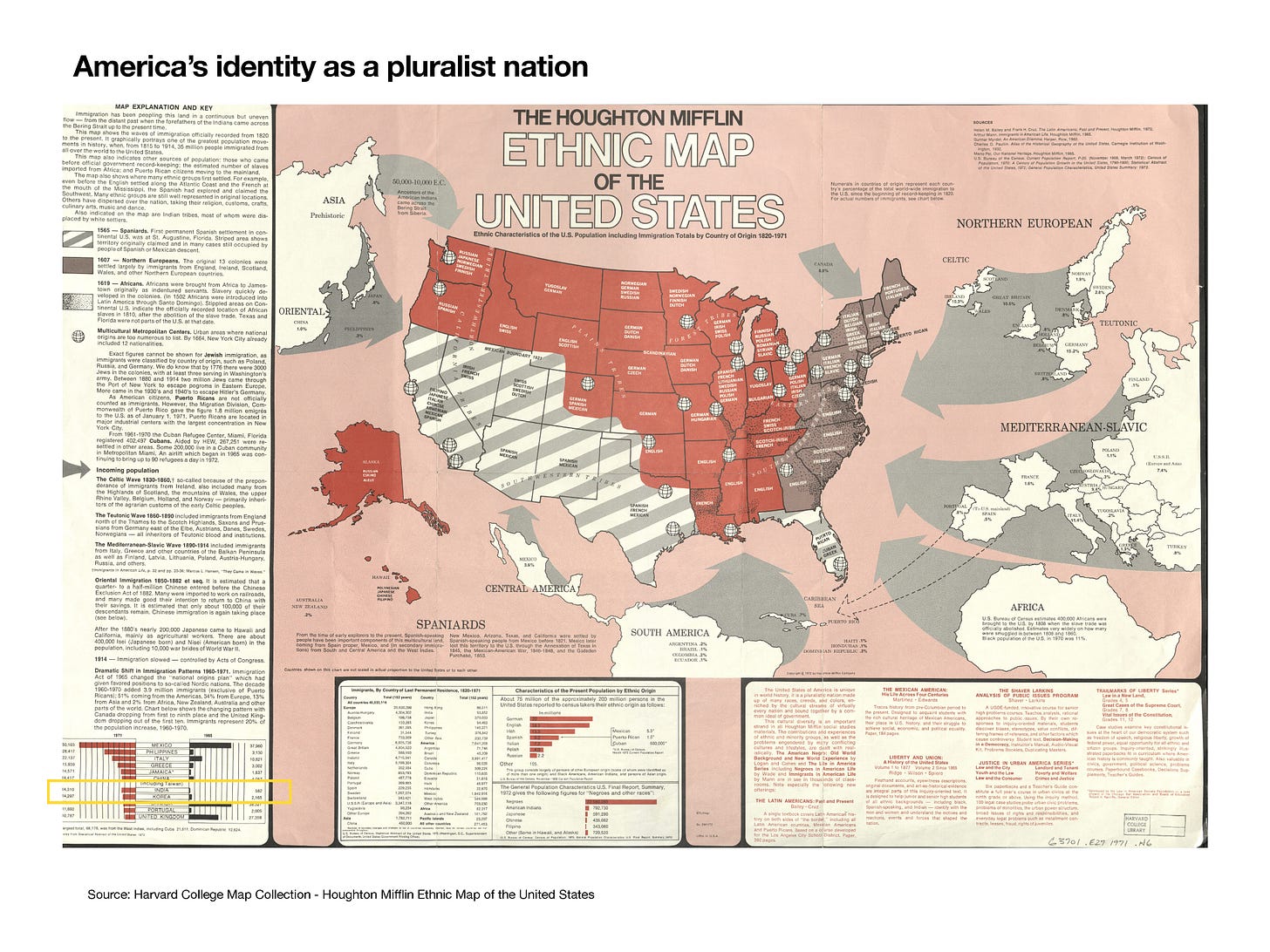

Migrant Middle proposes an alternative reading of American suburbs and small-town environments. Historically, American suburbs had been linked with terms such as ‘white flight,’ concerned with racial and spatial segregation. This meant that if ethnic (Indian, for example) populations settled in downtown areas of cities, the majority ‘white’ population effectively moved away. The suburb maintained itself for those of ‘white’ middle-class privilege that had the financial resources to buy a single-family house and a car. As a homogenous region, the suburb was car-centric, its housing stock primarily contained single-family homes, and a change in live/work patterns characterized such a way of life.[2] Due to these factors, among others such as redlining and biases/preferences with the home mortgage loan industry[3], the American suburb served to perpetuate issues of social and class division. Following the consequences of ‘white flight’ from cities in the 1950s and 60s, suburbs began to diversify. This was a time when the Cold War, the Civil Rights Movement, and the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act had been written into law. Suburban areas were frequently becoming “ports of entry or zones of emergence” for immigrant populations. Tech workers, IT call center experts, doctors, motel owners, gas station and shop owners, the suburb was a prime settling ground for Indians looking for opportunity.

Migrant Middle imagines suburbs and small towns as regions that “offer a space of freedom, imagination, escape, and fantasy; they are places for the consumption of the globally produced [and] locally assembled.”[4] This idea has been researched from various diasporic points of view, including Wen Li on general theories of the “ethnoburb”, Anthony D King on suburbs as spaces for global culture, Alan Berger on suburban futures envisioned through a plethora of modes (from technology, culture, autonomous living, etc), among numerous others who have led me into this research.

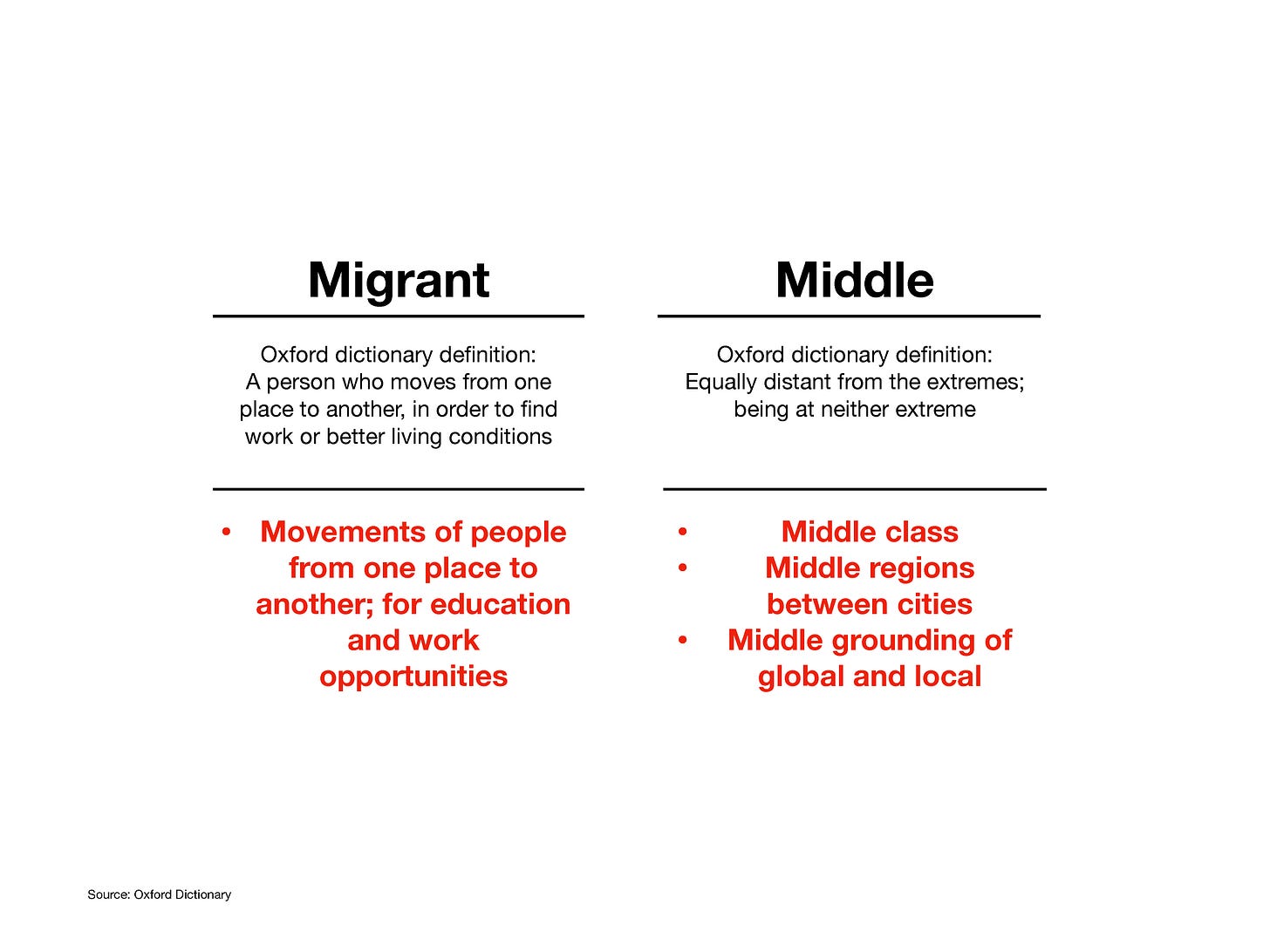

Migrant

The Indian diaspora has migrated in successive waves that were opened and closed based on ongoing immigration policy and periods of reform.[5] The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 transformed American immigration policy - expanding the countries of origin to the majority world and administering a selection process based on skill, merit, and education. The trajectory of American immigration policy forms the basis for what I describe as ‘migrant.’ I relate the movements of people from India to America, to educational and/or employment opportunities. Through this definition, I hope to uncover what such opportunities present for ‘second, third, and future’ generations of Indian-Americans as an extension of the ‘first-generation’ migrant experience.

Middle

Grounding of global and local

The relationship between inter-generationality and diaspora is significant in the American context, and the term ‘middle’ seeks to classify existing and new forms of conservation as they relate to the connection of global worlds and local places. How will the built environment interact with the ongoing need to conserve heritage practices (ritual, worship, traditions)? Will we adapt social and economic policies to accommodate heritage practices and ways of life? The introduction of a middle-ground solution is what I believe needs to be implemented.

Regions between big cities

Related to suburbs and small-towns, the term ‘middle’ comes from its meaning as a “sharp distinction between city and country remaining from prior urban settlement.. quickly obliterated and replaced by a middle landscape of suburban and ex-urban development.”[6] The middle regions between cities contain their own organizations of public and private spaces, built forms, and natural landscapes, which deserve to be analyzed as important aspects of American life. Given the presence of diaspora throughout middle regions and landscapes, we can indeed “recognize the middle landscape as a real locus of growth and innovation – rather than trying to make it in the manner of somewhere else.”[7]

Middle Class

The American middle-class[8] is significant as a classification of the world ‘middle’. The middle class, which was “once the economic stratum and clear majority of American adults, has steadily contracted in the past five decades,”[9] is shrinking and accompanied by an increase in upper- and lower-income tiers. Even though these changes have occurred gradually, the income gap brings about growing concern for equal access and opportunities for upward mobility that the American Dream[10] has always promoted. The pairing indicates that the suburb can be read as a complex region of networked identities, rather than a static zone of single-family dwellings and big box shopping malls.

[1] The Economist. “India’s Diaspora Is Bigger and More Influential Than Any in History.” The Economist, 16 June 2023, www.economist.com/international/2023/06/12/indias-diaspora-is-bigger-and-more-influential-than-any-in-history?utm_medium=social-media.content.np&utm_source=linkedin&utm_campaign=editorial-social&utm_content=discovery.content.

[2] Alan Berger, Joel Kotkin, and Celina Balderas-Guzmán, “Suburbia as a Class Issue” in Infinite Suburbia, ed. Joel Kotkin, (Hudson, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2017).

[3] See Chapter 6 for an expansive history and recollection of the effects of white flight and racial segregation in American cities and suburbs; Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, First edition., Democracy and Urban Landscapes (New York; London: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2017).

[4] Anthony D. King, Spaces of Global Cultures: Architecture, Urbanism, Identity, Architext Series (London; New York: Routledge, 2004), 106.

[5] Sanjoy Chakravorty, “Short History of Small Numbers,” in The Other One Percent: Indians in America, Modern South Asia Series (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016), 5-15.

[6] Peter G. Rowe, Making a Middle Landscape (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1991), 3.

[7] Peter G. Rowe, Making a Middle Landscape (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1991), 291.

[8] According to the US Census Bureau narrative on the ‘middle class’, there is no official definition. The Census Bureau derived the term from measures related to income distribution and income inequality (both accounts taken per household). Source: “Narrative on Income Inequality (Middle Class),” Census.gov, accessed May 3, 2022, https://www.census.gov/topics/income-poverty/income-inequality/about/middle-class.html.

Research methodology conducted by the Pew Research Center indicates Jesse Bennett, Richard Fry, and Rakesh Kochhar, “Are You in the American Middle Class? Find out with Our Income Calculator,” Pew Research Center (blog), accessed May 3, 2022, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/23/are-you-in-the-american-middle-class/.

[9] Rakesh Kochhar and Stella Sechopoulos, “How the American Middle Class Has Changed in the Past Five Decades,” Pew Research Center (blog), accessed May 3, 2022, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/04/20/how-the-american-middle-class-has-changed-in-the-past-five-decades/.

[10] “A Brief History of the American Dream | Bush Center,” A Brief History of the American Dream | Bush Center, accessed April 9, 2022, http://www.bushcenter.org/catalyst/state-of-the-american-dream/churchwell-history-of-the-american-dream.html.